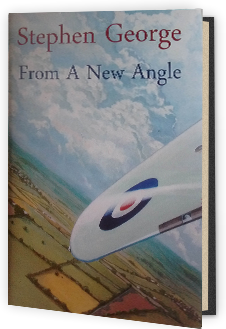

From a New Angle

Hardback: 144 pages

Ghost-written on behalf of the autobiographer’s client.

FROM A NEW ANGLE was a paid commission. Over a period of six-months, Rebecca’s client recorded seventeen hour-long interviews with Stephen, his grandfather, in London and passed each audio file onto Rebecca to type up, re-order and copy edit, to form a flowing, chronological story on paper. Since its publication, it has been added to RAF libraries and - like Royle's previous WWII book, BEING ERNEST - has been archived indefinitely at the Imperial War Museum, thus making it available for study.

Stephen George worked his way up from factory worker to RAF officer, experiencing many an adventure and brush with death while flying Lancaster Bombers in World War Two. He completed two tours and received two medals from the King for his incredible war effort, before going on to fly Stirlings in Transport Command and settle into family life in Enfield. A cheeky, humorous Cockney, Stephen is now 93 and sharing his life story in full for the first time.

The first print-run of FROM A NEW ANGLE was released in December 2015.

Reviews

I am responsible for acquiring this Department’s collections of papers relating to the RAF. I have today, spent some time reading through large sections of [Stephen George's] memoir, painstakingly compiled by yourself and Rebecca Royle and am pleased to confirm that it is indeed suitable for permanent retention in our archives. Extensive and detailed, and yet imbued with a conversational tone throughout... it neatly puts his experiences in the context of the events of the War and will, I am sure, be appreciated by our researchers (to whom life in RAF Bomber Command- especially in light of the forthcoming Second World War anniversaries- is proving to be of sustained interest). Consequently, ‘From A New Angle’ will now be catalogued under his full name and made available for study.Ellen Parton, Archivist, Imperial War Museum

Feedback from the client:

I had a read of the first couple of chapters last night, and have to say - it's WONDERFUL. Really really happy with how it's turned out - you have done a remarkable job pulling together all his stories into something that flows nicely and really sounds like him. I guess my biggest concern before starting the book was that it could sound like disparate anecdotes stitched together, but you have managed to turn it into one narrative, which is a real achievement.Client

An excerpt: From a New Angle

…We successfully bombed the target and had turned around to leave. By the time we’d flown into the outside of the defending area – just by the Ruhr – we expected that the threat of getting Flak had passed (‘Flak’ came from the German word for the anti-aircraft gun – Flugabwehrkanone – which slung shells up from the ground).

Squadron Leader Davies said, ‘ah well, that’s that.’

Just as soon as the words had left his mouth, there was a tremendous bang. We’d been hit by a shell burst, right in front of the nose! A Flak splinter flew up and Davies received a blow to the head, cutting his helmet from front to back and splitting his head an eighth of an inch deep from front to back in the process. He was knocked unconscious with the force and the plane suddenly went into a screaming dive. The plane hadn’t gone into a dive by accident – Davies hadn’t been flown forward, because he was strapped in; rather, he’d instinctively put the plane into a dive upon the moment of impact with the shell, because he was operationally experienced and he knew what to do if the plane was hit.

At that point, I simultaneously realised that a piece of Perspex from the window was lodged in the back of my neck, forming a little bleeding cut about a quarter of an inch long. It didn’t bother me very much though because, although the neck is a sensitive area, I had a job to do…

I pulled back hard on the control column, which was ringing out. I looked and saw the airspeed indicator approaching 400mph, which is going some for a Lancaster and thought, ‘oh God, the trim! The trim!’ realising that the trimming wheel had fallen off.

The trimming wheel moves the big control flaps on the wings and the tail, pushing them in the opposite direction to balance the thing.

I quickly wound back on the trim and with quite a job, we came out of the dive. Whoa, yes! Thank God for that, because it would have made an awful hole in the ground!

Once we were levelling up again, it was established that it was just Davies and I that had been injured. The bomb aimer and the navigator moved quickly to get the skipper out of his seat and onto the floor. While still flying the plane, I had to face away from the control column, looking backwards, not only to give them room to get by, but also to eye up the tailplane – also known as horizontal stabilizer – with the horizon, trying to keep the plane level. With my back to the instrument panel, I could only reach out with my right hand for the control column.

Eventually, they got a completely unconscious Davies onto the floor and I was able to jump back into the seat. We had the new standard compass on our Lancaster, the ‘gyro’, which was easier to read than the magnetic compass fitted as standard to all other aeroplanes. With the aid of that, I managed to keep a straight course over the North Sea and over the coast. We continued to fly down country, towards our base.

The skipper, having being made reasonably comfortable, came around and wouldn’t let me land the plane. There was blood all down his face but he insisted on landing it himself. We changed places and, as we were coming in, he said, ‘I can’t see a bloody thing, George. I can see three runways.’

So I offered: ‘land on the middle one, Sir.’

Davies took that tongue-in-cheek advice and did his usual perfect landing, before promptly passing out again, near the end of the runway.